Frank Walls is scheduled to be executed on December 18. The U.S. Supreme Court has made clear for over two decades that the Eighth Amendment categorically prohibits executing people with intellectual disability. For nearly as long, Walls’ case has been one of the clearest examples of how Florida’s death penalty machinery ignores that mandate — trapping a man with lifelong cognitive impairments in a system designed to deny meaningful review.

On November 25, Walls’ lawyers filed a Successive Motion to Vacate his conviction and sentence, along with a Motion for Stay of Execution, noting that his warrant was signed under a schedule so truncated it cannot support due process. The defense explains that “the abbreviated schedule… does not allow Mr. Walls to appropriately address the constitutional issues raised in his successive motion.” And because of the Thanksgiving holiday and weekend, 11 of the 30 days of the warrant period — more than 1/3rd of Frank’s final month alive — he is barred from communicating with counsel. Frank Walls deserves this meaningful review. Florida is giving him the opposite.

None of this is meant to make light of the grief and pain caused by Frank’s actions. He was sentenced to death for the 1987 murder of Ann Peterson, and is serving a life sentence for the murders of Edgar Alger and Audrey Gygi. These were tragic crimes, and the collective suffering of their families deserves our deepest sympathy. But justice demands the highest standard of review. When our state executes a person with documented intellectual disability, it ignores both constitutional safeguards and basic human dignity. Justice demands more than carrying out a sentence; it requires ensuring that our most vulnerable citizens are protected, not condemned.

A Child Marked by Disability and Decline

Frank grew up in a close-knit family. As he helped care for his brother, who had a disability, teachers repeatedly raised concerns about Frank’s cognitive delays.

School records and the trial court’s Sentencing Order documented years of red flags:

- He was placed in emotionally handicapped classes due to emotional outbursts linked to underlying neurological issues.

- Psychologists observed “apparent brain dysfunction” reflected in his difficulty learning math and language.

- At age six, he was diagnosed with ADHD and tested with a full-scale IQ of 88.

- At age twelve, he suffered two bouts of viral meningitis requiring hospitalization. Experts later testified that this condition can cause serious and lasting brain damage.

- By age fourteen, test results showed declines in his verbal functioning.

- As he moved through adolescence, he bounced between special education programs, and his functioning deteriorated further.

This is not the developmental history of someone the Constitution permits a state to execute.

The First Trial Was Reversed for Competency Issues

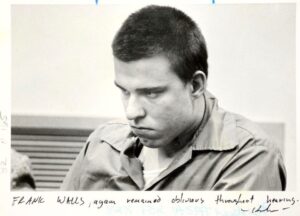

Frank was just 19 when he was arrested for this crime. His first conviction and death sentence were reversed because the trial court failed to properly evaluate whether he was competent to stand trial. The unresolved questions about his ability to understand the proceedings and assist his attorneys were so serious that the Florida Supreme Court vacated the entire judgment and ordered a new trial.

Source: NW Florida Daily News

Evidence of Intellectual Disability Deepened Over Time

Before his second trial in 1991, a new evaluation placed his full-scale IQ at 74. Experts would later testify that the several bouts of meningitis were very likely to be the cause of the drop in IQ, that that drop almost certainly occurred shortly after the illness, and certainly before the age of 18. Even his trial court recognized the severity of his decline, finding that his IQ “decreased from the time he was school age to the present,” dropping from “Average” to “Low Normal.” One expert testified Frank was “extremely immature,” functioning intellectually like a 12- or 13-year-old.

After Atkins v. Virginia (2002), Walls again pursued relief, as was his right. In 2006, the State’s own expert tested him and found a full-scale IQ of 72, confirming that his score had been stable for nearly 15 years and fell directly within the range requiring further intellectual-disability analysis. He never received it.

Hall v. Florida Should Have Protected Him — Florida Took It Back

In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Hall v. Florida, striking down the rigid IQ cutoff Florida had used to deny Frank and many others the opportunity to prove they were constitutionally ineligible for execution. Hall required the State to examine:

- Subaverage intellectual functioning

- Adaptive-behavior deficits

- Onset before age 18

In 2016, the Florida Supreme Court ruled, in Frank Walls’ own case, that Hall applied retroactively. Frank was finally granted the evidentiary hearing he was entitled to. But, because of unavoidable discovery delays and the COVID-19 pandemic, the hearing did not occur until 2021.

In the interim, in 2020, Governor DeSantis’ newly appointed majority of the Florida Supreme Court abruptly reversed course, ruling that Hall is not retroactive after all. This functionally erased the Court’s own 2016 ruling in Frank’s favor. The State immediately tried to stop Frank from receiving the hearing at all, but the Court allowed it to proceed. Little did Frank know, the hearing would actually be a sham proceeding where the outcome was pre-determined.

At the hearing, Frank’s lawyers called multiple experts who offered extensive, and largely unrebutted, evidence of lifelong disability, brain damage, dramatic IQ decline due to adolescent meningitis, and profound adaptive deficits. Frank’s former trial attorney testified that even in the early 1990s — long before Atkins even existed — he believed Frank was intellectually disabled. The State’s own expert conceded that he had adaptive deficits, and that his score was in the qualifying range.

Despite all of this solid evidence, the trial court denied relief. The lower court agreed with the State that the 2020 reversal from the Florida Supreme was a basis to ignore the evidence and reject the claim solely because of this procedural time bar.

This is equivalent to Frank being actually innocent of the death penalty (since he is categorically barred from execution) but the courts saying it doesn’t matter because when he first raised the claim, the law was not in his favor, and thus he was too late. This is the same as if Frank had somehow discovered that due to a mix up in his birth records, he was in fact under the age of 18 at the time of his crime. But, instead of the court saying, “Sorry, we know you are not legally eligible for the death penalty,” they said, “Sorry, but you brought us this proof too late so it’s okay to execute you.”

Others were denied relief on the same basis, including David Pittman, who was executed this year.

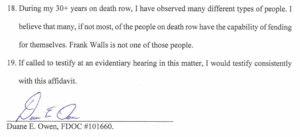

Testimony From a Neighbor on Death Row: Frank Tried Every Day

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence in Frank Walls’ intellectual-disability claim comes from someone who knew him better than nearly anyone inside the prison system: his fellow death row inmate Duane Owen. Duane lived next to Frank on death row for nearly 30 years before he himself was executed in 2023, and his affidavit paints a picture of a man who was not only impaired, but also trying, every single day, to navigate a world designed for people with far greater cognitive ability.

Owen wrote that:

- He had observed Frank “for nearly 30 years” across day-to-day interactions on death row.

- Frank struggled with letters, reading comprehension, and understanding basic written material.

- Teaching Frank simple tasks was “like trying to teach a kindergartener.”

- Although Frank could read individual words, he often could not understand what he had just read, frequently asking questions that showed he missed the entire meaning.

- Frank “talked to himself for hours,” a behavior Owen had witnessed repeatedly.

What is equally important, and often overlooked, is the context of Owen’s testimony: Frank asked for help. He wanted to learn. And people around him were willing to help him. This is really common for people living with an intellectual disability. They have adapted to rely on the kindness of others around them, and they know how to appear higher functioning than they actually are, so they fit in. It is known as the “cloak of competence.”

Owen explained that he “often assisted” Frank with daily activities and basic functioning. That means:

- Frank knew he needed help.

- He asked for help.

- He tried to understand.

- And those around him recognized how profoundly he struggled and still chose to help him.

In a place as isolating and unforgiving as Florida’s death row, building that kind of trust — and seeking assistance — is itself evidence of effort. Frank relied on others not because he was lazy or indifferent, but because he simply could not function independently.

This is not the behavior of someone choosing not to try. It is the behavior of someone who is doing the best he can with significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, just as the Constitution describes in Atkins.

A Second, Independent Constitutional Crisis: Florida’s Execution Protocol Puts Frank at Grave Risk of Torture

Frank’s intellectual-disability claim alone makes his execution unconstitutional. But the danger does not end there. Even if Florida were somehow permitted to pursue an execution — despite decades of evidence showing he meets the Atkins criteria — Frank Walls has also brought a separate claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 demonstrating that the State’s current lethal-injection protocol poses an intolerable and unnecessary risk of severe pain. This claim underscores a second, parallel truth: Florida is preparing to carry out an execution using a procedure it cannot reliably administer, on a medically fragile man whose body makes that procedure especially dangerous.

Through his federal counsel, Frank has shown that his chronic and worsening medical conditions, caused in large part by nearly 40 years in prison, make the State’s etomidate-based protocol uniquely likely to cause torment rather than unconsciousness. Testimony from lethal-injection expert Dr. Joel Zivot explains that Frank’s declining cardiopulmonary function, untreated sleep apnea, hepatic insufficiency, and sharply reduced oxygen saturation levels mean that the first drug, etomidate, will interact with his compromised physiology in a devastating way. Instead of inducing stable unconsciousness, the drug is likely to trigger rapid pulmonary edema: the sensation of suffocating on one’s own fluids while fully aware. The second drug, a paralytic, would freeze his body in place — masking any suffering he experiences while preventing him from breathing on his own.

This is not speculation. It is rooted in documented medical findings, decades of clinical literature, and the expert’s direct evaluation of Frank just months ago. For a man whose intellectual limitations make it difficult to advocate for himself, the risk of a torturous death hidden behind paralysis is a profound Eighth Amendment concern.

The State’s Own Records Reveal a Pattern of Errors and Irregularities

Frank’s § 1983 claim does not rest solely on his medical vulnerability. His legal team has uncovered evidence directly from the Florida Department of Corrections’ own pharmacy records and lethal-injection logs that should alarm anyone who believes executions must be carried out with precision.

Those logs show that during this year’s execution spree, prison pharmacists repeatedly recorded withdrawing only one-half to one-third of the required lethal-injection drugs before executions. In several instances, the documentation reflects that the medication was not even removed from the pharmacy until the day after the execution occurred. These are not minor clerical mistakes; they suggest fundamental breakdowns in drug preparation, chain of custody, and verification protocols.

The consequences are not theoretical. During the execution of Bryan Jennings, witnesses observed prolonged movements and a delayed pronouncement of death — signs consistent with inadequate sedation or incomplete dosing. If pharmacists were routinely failing to withdraw the full amount of medication, Jennings’ distress may not have been an anomaly at all, but a symptom of a system operating without reliable safeguards.

Moreover, Florida’s own drug logs show that in four executions in 2025 — Curtis Windom, Kayle Bates, David Pittman, and Victor Jones — the State used etomidate that had expired months earlier on January 31, 2025. The pattern is stark. Florida repeatedly administered an expired sedative to condemned prisoners, raising serious concerns about potency, the risk of consciousness, and the basic reliability of the protocol it relies on to carry out the law.

Other states have halted executions entirely when confronted with comparable evidence of record-keeping and pharmacy management failures. Florida has instead accelerated its schedule.

A State Rushing Forward While Systems Fail

These irregularities raise a simple but urgent question: if Florida cannot keep accurate records of the drugs it uses to kill, what else is going wrong in the chamber?

For Frank Walls, a man with documented intellectual disability, severe medical decline, and an unresolved constitutional claim, these errors multiply the risks. He is not just vulnerable. He is uniquely susceptible to the very complications that Florida’s flawed protocol is most likely to produce: incomplete sedation, unrecognized consciousness, and suffocation masked by paralysis.

And yet, instead of pausing to investigate or ensure that its process meets constitutional standards, Florida is speeding ahead under a 30-day warrant that denies Frank the opportunity to litigate either of his claims meaningfully. A man the Constitution protects is now being pushed toward a procedure that could amount to torture.

Frank Walls Should Not Be Executed

Frank Walls has lived with lifelong cognitive impairments, brain damage, declining IQ scores, and clear adaptive-behavior deficits. All of this was documented long before Hall, long before Atkins, and long before this execution date.

The constitutional bar on executing people with intellectual disability is unambiguous. The problem is not the law. It is Florida’s refusal to follow it.

If Florida executes Frank Walls on December 18, it will not be because the Constitution permits it. It will be because the courts closed their doors to him — first through rigid rules, then through retroactivity reversals, and now through a rushed, 30-day warrant period that makes meaningful review impossible.

Florida is preparing to kill a man who meets the criteria for intellectual disability — a man the Constitution says cannot be executed. It is a failure of law, medicine, and basic humanity.